The "Bottom-up Value Chain" Framework

How to Avoid the Worst Mistakes Brands Make When Setting Their Value Chain (Ending Up With a Beautiful Bottle Nobody Wanna Buy).

Dear Drinks Builder,

In today’s issue, I’ll share my three-step process for improving your approach to creating your value chain.

I don't have a silver bullet for the perfect one, but I can guide you on what you should consider when creating one. By adopting this process, you’ll ensure it works bottom-up for all the links in the chain.

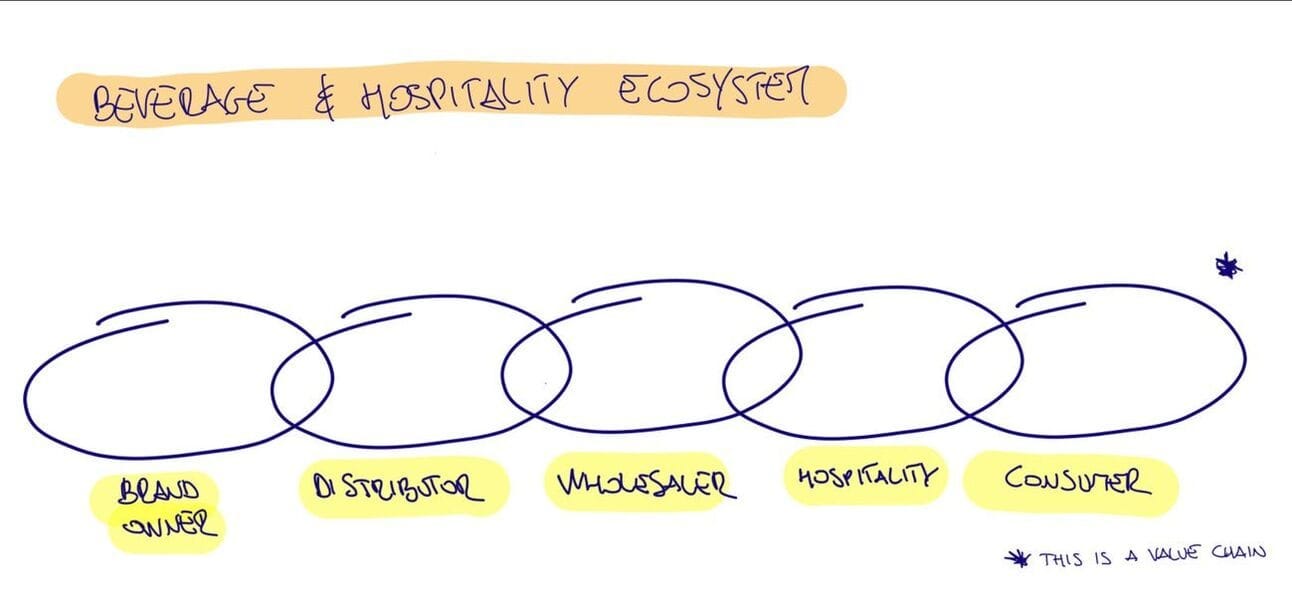

Unfortunately, most people forget to consider the whole drinks ecosystem. This way, they forget who to give (enough) margins to because they think top-down.

Value chains start from the glass, not from the distillery.

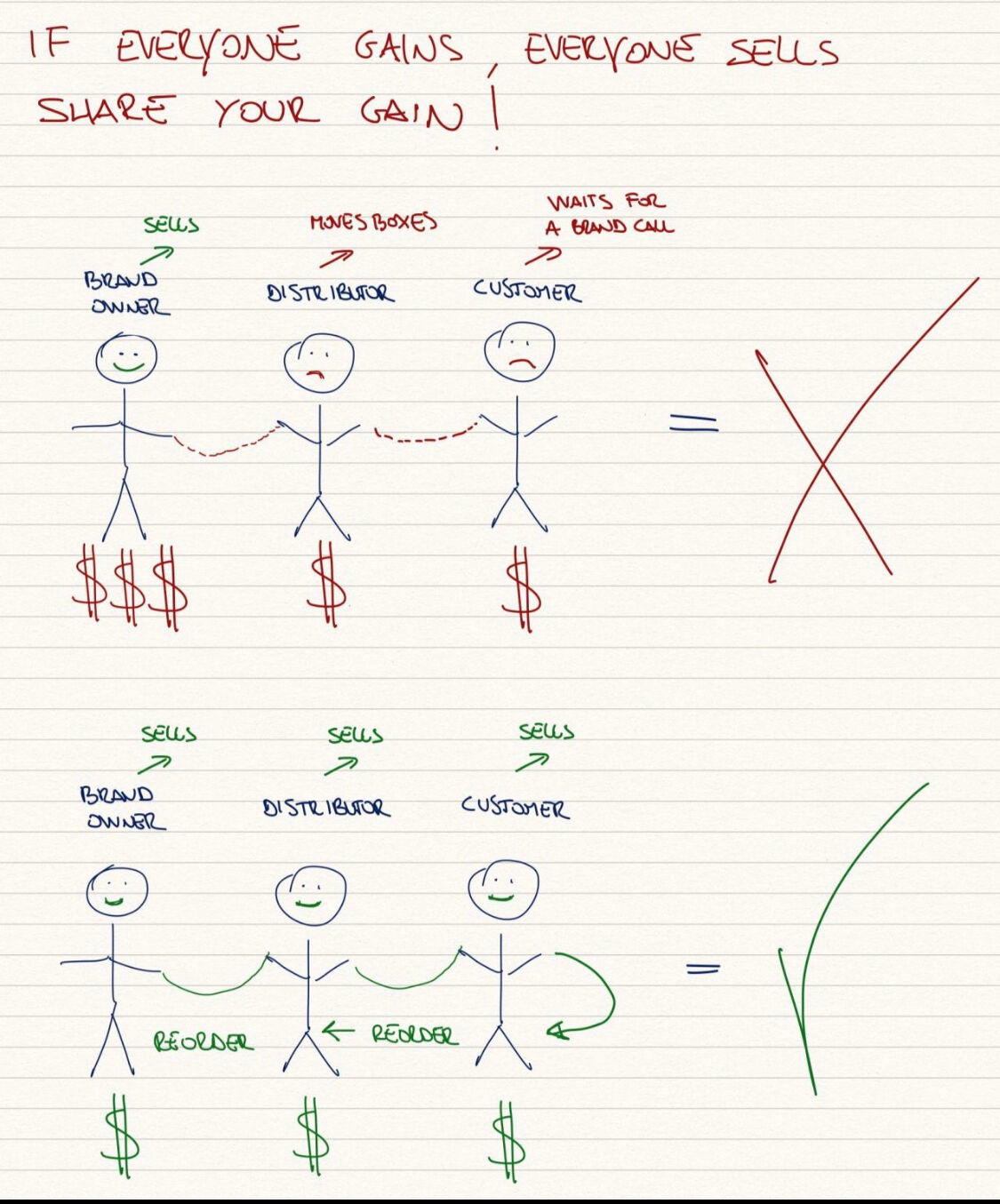

It's not about how much you want to earn; it's about what the market can absorb. There is a glass ceiling in what consumers, bars, etc., are willing to pay for a brand. What you bring to the table drives how much you can stretch that (recommended) price ladder. If you can't drive people to pay more for your product, you must live with the value you manage to get and share it with the ecosystem. Without acknowledging that, your brand will lack a rate of sale.

You may manage a good sell-in but lack sell-outs and reorders if you are good at sales. So, why does this happen?

Challenge 1: You forgot to account for wholesalers' margins

Brands often create a value chain that considers only one line for someone who will bring it to market on their behalf.

That line is usually named "distributors," but that’s a vague word that doesn’t include all the parties involved in distribution.

When selling in their market, that distributor is usually a wholesaler that brings their brand to market. When exporting, you must account for two lines: importers and wholesalers.

Brands often don't realize that an importer has only a small sales force and that most of the city's sales will happen through wholesalers. If you don't make room for another line on your value chain, the importer or the wholesaler will not have enough margins and will not push your brand. They may stock it but do nothing more than move boxes.

Challenge 2: You built your value chain top-down with the wrong COGS, overheads, and other costs.

Brands are created in-house, but they are built in the market.

Often, brands have too high expectations, creating an unrealistic brand. This happens with expensive ingredients, production costs (especially with third parties), bottle design, etc. (COGS = Cost of Goods).

Another common mistake is creating a team that is too big and has too many overheads (e.g., a comprehensive founding team, salespeople, brand ambassadors, etc.).

That brand will end up at a high price not because of its actual value but because of wrongly calculated costs.

All these costs pile up, and after adding excise, taxes, and everyone's margins, the product ends up on the shelf at a crazy price that no retailer or consumer will be interested in.

Challenge 3: You want to retain too much margin

The issue with creating a brand top-down is that it makes you cocky. It makes you think people will love your brand and accept your recommended price because it is the best in the market.

That approach pushes you to procrastinate, treating value chain issues as if you kick a can down the road.

"I want to keep this margin, so I'll sell at this price" makes you pass the issue down to the following link in the chain. The problem is that if everyone thinks like that, you end up at an unacceptable shelf price.

You may be lucky and sell your first order to a distributor or an importer, but it's just a matter of which link of the chain wakes up first and stops ordering, and the issue will climb back the chain. Your brand gets stuck in some warehouse without any more pull.